A Cure for Nihilism? | Everything Everywhere All At Once

The philosophy of the 7x Oscar-winning movie

Everything Everywhere All At Once is a movie about family and Nihilism. It's about the wounds that we inflict from one generation to another. And it's also about the crisis of meaning that is corroding our mental health as individuals and as a collective.

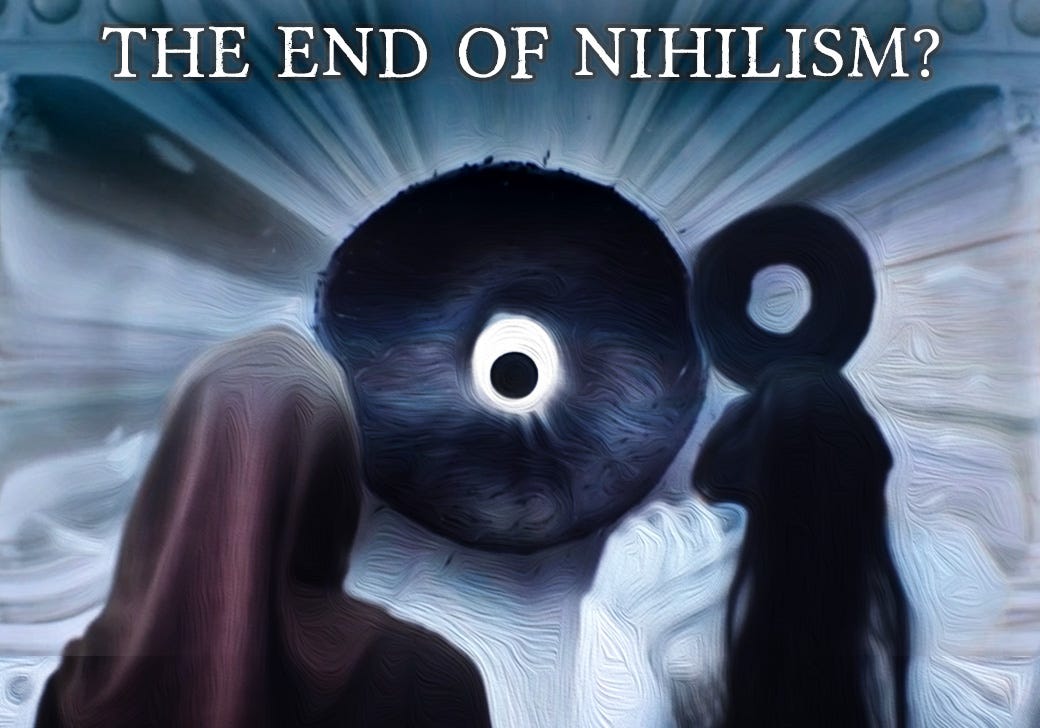

The black bagel is the symbolic heart of the movie. It's a bizarre image that captures the internet-era Nihilism better than anything else out there. But the movie doesn't just show what Nihilism looks like, it looks for its deeper roots and even prescribes a cure for the meaning crisis. And while this antidote comes up short, I see it as a step closer to the solution than Existentialism or Absurdism.

This movie has something really important to say about Nihilism which cuts past the edgy intellectualism that this philosophical worldview wears as a mask and gets closer to the real crisis lurking beneath and behind this intellectual façade of Nihilism.

The movie tells the story of a Chinese-American immigrant family who own a laundromat somewhere in America. There's the main character Evelyn, her husband Waymond, their daughter Joy and Evelyn's father Gong Gong. The three core characters of wife, husband and daughter are each struggling with their own crisis at the start of the movie. Evelyn is overwhelmed by their laundromat business — which is being audited by the IRS; Waymond is struggling with his relationship with Evelyn and has gotten divorce papers in a desperate attempt to save the marriage; and Joy is going through more of a general internet-era Nihilistic meltdown that is amplified by the liminality of being a second-generation immigrant.

As the movie progresses it turns into an absurd sci-fi adventure into the multiverse. We are taken from the everyday reality of the laundromat and the IRS building into a massive multiverse where we discover that the daughter Joy's parallel selves have merged into a seemingly insane omniversal villain called Jobu Tupaki who is every version of Joy in the multiverse:

"I am your daughter. Your daughter is me. Every single version of Joy is Jobu Tupaki".

Some see this use of the multiverse as a lazy plot device and compared the movie negatively with Marvel. But from an Integral or Metamodern perspective this metaphor of the multiverse is a perfect way of illustrating the multiplication of perspectives that characterises the Postmodern stage of cultural development.

It's even more appropriate as a metaphor for the internet which has divided our attention and fragmented our minds — dragging us further and further from our original material universe into a virtual multiverse of infinite possibility and opportunity. Through the internet in general and social media specifically we see all our unlived lives displayed to us through our network. We see everything that we could be, should be, won't be but want to be and it crushes our lives into a half-baked simulacra of something better we see online.

And this journey through the looking glass of our phone screens into the fragmentation of the multiverse brings us to the central symbol of the movie's Nihilism: the black bagel.

The Black Bagel

In approaching the philosophical core of Everything Everywhere All At Once, everything leads to the black bagel. It is the iconic and lasting image of the Nihilism that the movie is wrestling with. The black bagel is the in-your-face-multiverse-special-effects Nihilistic crisis of the internet age.

But this multiversal symbol of meaninglessness is mirrored by more everyday symbols. The circular bagel with the hole in the middle reminds us of the symbol of the ouroboros — a snake devouring its own tail which is an ancient symbol pointing to the cyclical nature of life, death and rebirth.

Taking place on the eve of Chinese New Year, Everything Everywhere All At Once directly invokes this cyclical theme. As Evelyn puts it later in the movie when she has been fully consumed by the Nihilistic crisis:

"Another year, pretending we know what we're doing, but really we're just going around in circles".

When we first meet Joy she is staring into the drum of a washing machine which is a pit of black with a bit of white floating around directly mirroring the black bagel. The cyclical humdrum of the washing machine — like the cyclical turn of the year — evokes the same sense of meaningless repetition.

Both the washing machine and New Year function as symbols of this cyclical repetition of time that has lost all meaning. It brings to mind the myth of Sisyphus which Existentialist philosopher Albert Camus uses as the image of Nihilism in his Existential classic The Myth of Sisyphus. The ancient Greek hero Sisyphus was punished by the gods to roll a boulder up a hill and when he had reached the top to watch it roll right back down again. Sisyphus then had to return to the bottom and roll the rock right back up again repeating the process again and again until the end of time. For Camus this is the experience of Nihilism. We keep going forward lying to ourselves that things are getting better pretending we know what we're doing but really we're just going around in circles.

In the context of the movie, the cyclical pattern that we are most concerned with is the cycle of the generations. The Nihilistic crisis makes this seem pointless. It seems that the only thing passing through the generations is a repetition of the same wounds — a never-ending cycle of misery just like the Indian idea of Samsara.

We also meet the black circle with the white centre in the IRS offices when the auditor Deidre draws a big black circle on one of the receipts. As the washing machine represented Joy's crisis, this IRS receipt represents Evelyn's. We can see Evelyn's spirit being crushed by the inhumane boulder of bureaucracy. Benjamin Franklin once joked that nothing is certain in this life but death and taxes. This pessimistic note is what is being evoked by the IRS receipt — Evelyn is trapped in what Henry David Thoreau called "a life of quiet desperation".

Later as Evelyn falls into her own Nihilistic crisis we see this receipt fall into the black bagel. That is the moment when her mundane existential crisis dissolves into the cosmic Nihilistic one. She stops caring about the business or about taxes. She tells Deidre to shut up, she signs the divorce papers and takes a baseball bat to the laundromat saying she always hated the place. This is what happens when things fall into the black bagel: they lose all meaning.

And that brings us to the black bagel itself. The bagel was created by the omniversal villain version of Joy — Jobu Tupaki. When she meets our Evelyn for the first time Jobu Tupaki shows her a white room like an altar in a church or a temple and behind the curtains — the holy of holies in this temple of Nihilism is the black bagel. She tells Evelyn how it came to be:

Jobu: “I got bored one day and put everything on a bagel; everything. All my hopes and dreams, my old report cards; every breed of dog; every last personal ad on craigslist; sesame; poppy seed; salt. And it collapsed in on itself. Because you see when you really put everything on a bagel it becomes this. The truth." Evelyn: "What is the truth?" Jobu: "Nothing matters"

So the black bagel then is Everything Everywhere All At Once. It makes the implied meaninglessness of the washing machine explicit. The black bagel is the classic Nihilistic crisis of the washing machine amplified by the multiversal experience of the internet. The multiversal Jobu Tupaki has seen free will — the last bridgehead against Nihilism — washed away. For every choice she ever made, there's another Joy somewhere else in the multiverse who chose differently. Every possibility exists somewhere else in another universe and so everything that happens is just random; it's just physical atoms smashing around generating a realm of infinite possibility. Nothing matters because everything is just a "statistical inevitability".

This is a familiar crisis for us citizens of the internet age. If you have an idea, someone else on the internet has probably already thought of it; if you want to go somewhere there's no doubt that one of your friends on social media has already been there and taken beautiful photos. There's nothing you can do, nowhere you can go, nothing you can learn or become that someone out there hasn't already done and in all likelihood done better than you ever could. It's just a statistical inevitability. The vastness of the internet crushes us down to tiny insignificant little nothings.

The black bagel is the living symbol of the collective crisis of Nihilism — sucking the life out of our culture. As the Waymond from another universe — the Alphaverse puts it:

Alpha Waymond: "She's been building something. We thought it was some sort of black hole but it appears to consume more than just light and matter. We don't know exactly what it is. We don't know what it's for. But we can all feel it. You've been feeling it too haven't you? Something is off. Your clothes never wear as well the next day; your hair never falls in quite the same way; even your coffee tastes...wrong. Our institutions are crumbling; nobody trusts their neighbour anymore and you stay up at night wondering to yourself" Evelyn: "how can we get back?"

This black hole is there even if we don't see it. Its effects suffuse every corner of the culture. This is the meaning crisis that affects us all whether we are conscious of it or not.

But this is where Everything Everywhere All At Once goes beyond a simple embodiment of an internet-age Nihilism because it doesn't just take the philosophy of Nihilism at face value but treats it as a mask — as a defence mechanism. Nietzsche once wrote that

"most of the conscious thinking of a philosopher is secretly guided and forced into certain channels by his instincts."

And this is the case with Nihilism. The Nihilist portrays themselves as a heroic warrior — one of the select few who can stomach the dark truth of reality. They have seen through the bullshit of society and they know that everything is meaningless:

Jobu: "I have felt everything your daughter has felt. I know the Joy and the pain of having you as my mother. Evelyn: then you know I would only do the right thing for you. " Jobu: "Right is a tiny box invented by people who are afraid and I know what it feels like to be trapped inside that box. The bagel will show you the true nature of things. You'll be free from that box just like me. "

But this heroic posture is a mask. Nihilism isn't a crisis arrived at philosophically; it's a personal emotional and psychological crisis which is manifesting as an intellectual Nihilistic philosophy. But this Nihilism isn't the wound; it's a symptom. There is something happening on an emotional level beneath this truth. It is easier and far cooler to see oneself as a truth-teller — as an overcomer of societal bullshit. The sarcasm and irony; the apathy; the condescension and the posturing is a cultural stereotype that has been created and imitated to deal with some deeper psychological condition or conditions that have made their appearance in the landscape of modernity and postmodernity.

When Jobu first shows Evelyn the bagel she tells her the liberation that comes with the bagel's revelation that nothing matters:

Jobu: "Feels nice doesn't it? If nothing matters then all the guilt and pain you feel for making nothing of your life goes away."

Later in the movie, when Evelyn finally comes around to Jobu's way of seeing things, we learn that the bagel wasn't a meaningless fruit of boredom — the creation of an apathetic Nihilist. It was an exercise in desperation revealing the true torture lying beneath the icy surface of apathy:

Jobu: "You know why I actually built the bagel? It wasn't to "destroy" everything. It was to destroy myself. I wanted to see if I went in could I finally escape. Like actually die. At least this way I don't have to do it alone."

At the peak of her own Nihilistic crisis, Evelyn is ready to join her. But this is not how the movie ends. Just before mother and daughter enter the void of the bagel, something catches Evelyn's attention. She turns to look at her husband dismissively one last time

Evelyn: Look at my silly husband — probably making things worse

But in this last look at Waymond she begins to see him for the first time. And it's at this point that we enter the domain of the movie's second great symbol; a symbol which the movie suggests can lead us out of the Nihilistic crisis and that symbol is the googly eyes.

Waymond and the Googly Eyes

Googly eyes are present in the movie right from the very first scene. Waymond puts them on everything despite how annoyed Evelyn gets by them. They are a symbol of Waymond's whimsy and his lighter approach to the world.

In a movie full of mistrusting, resentful and cynical characters, Waymond stands out as the exception. He is kind, patient, attentive, loving and accepting. While Evelyn is stressing over the IRS, her father and the party, Waymond dances with customers; he bakes cookies for the IRS auditor (despite her harshness to them); and even when he is looking to divorce Evelyn it is not because he is giving up or holds negative feelings towards her — it's a gambit to get her to focus on her crisis-oriented attention on the dire state of their relationship. Waymond is the embodiment of empathy, compassion, whimsy and unconditional love. And the googly eyes are his symbol. Where the bagel is black on the outside and white in the centre, the googly eyes are white on the outside and black in the centre.

For the majority of the movie Evelyn, along with everyone else, disregards her husband. But at the edge of Nihilistic self-destruction she finally sees him. She sees his kindness. She sees that he makes the world a better place. She sees that he is love and that love is the solution.

As the movie reaches its climax and Evelyn goes to save Joy from oblivion in the black bagel she no longer fights violently but putting a googly eye on her forehead — in the symbolically significant spot of the third eye — the now enlightened Evelyn despatches her opponents with love — giving to each what they want.

The Love that is the Answer

What Evelyn learned from Waymond — which is encoded in the symbol of the googly eyes — is that there is a different way to approach the problem of Nihilism.

The only solution that Joy and her mother could come up with by themselves was giving up. Confrontation with the black bagel left them with the sense that nothing mattered. That is because they were oriented towards the realm of structure, status and attainment. And so what the Nihilistic crisis means for them is that they are mediocre. When Joy talks about how she made the black bagel she starts with her goals and dreams, then her report cards and from there she leaps to every type of dog and every ad on craigslist.

But, as Waymond shows us, there is more to life than achievement and status. That's hard to remember in a world that is so oriented towards individualism. To be an individual means to be different — to be unique and to be special and to have some gift to offer the world that nobody else does. Individualism orients us towards the vanity of attainment.

But Waymond isn't oriented towards individualism — he's oriented towards people. He's oriented not by achievement but by love. But even love has been consumed by the individualism of modernity. When we seek love we seek it in romantic relationships — we are looking for "the One" who will complete us.

But the genius of Everything Everywhere All At Once is that it doesn't fall into this trap. The journey of the movie isn't for Evelyn to realise her love for Waymond — it's an essential part of her character arc but it's not the meaning of her journey. What Evelyn learns from Waymond is that love is the answer. But while love is the way, romantic love is not the wound that needs to be healed.

The wound of Nihilism is in the roots. Everything Everywhere All At Once is ultimately a movie about intergenerational trauma. It's about healing the wounds that bleed from generation to generation. Joy's multiverse adventure isn't about her relationship with her girlfriend Becky but a search for her mother.

Evelyn's journey in the movie is a fall and a rise. The IRS problem is put in perspective; the business is put in perspective. At the end of the movie Evelyn could go anywhere in the multiverse. She doesn't choose to be a great actress or singer or inventor or chef — the things she always dreamed of. She chooses to enjoy these "few shards of time where anything makes sense" with her family because nothing else matters. It's not that nothing matters but that structure, achievement and greatness don't matter. What matters is love. And not (just) romantic love but the multi-generational love of family.

My only criticism of Everything Everywhere All At Once is that it doesn't go far enough. As it excavates the deeper roots of Nihilism, it goes beyond the mask of Nihilism and the myth of romance only to stop digging at the level of the nuclear family. It's understandable since there is still something we can work with and heal at this level. But the alienation of modern life goes deeper.

Nihilism is the sickness of Modernity and Postmodernity. It is not just that we have become disconnected from our families but that we have lost the connection to community and the landscape and now with the internet we are even losing touch with the physical world. Once upon a time we were stitched into the landscape along with our ancestors, our wisdom and our gods. But with the increasing abstraction of civilisation we have become increasingly unrooted. The multigenerational traumas of the nuclear family provide a good starting point but that is all.

Everything Everywhere All At Once doesn't give us the ultimate solution but at least it points us in the right direction which is more than can be said for the sugar-coated lens of Hollywood and philosophies of freedom like Existentialism.

> Nihilism isn't a crisis arrived at philosophically; it's a personal emotional and psychological crisis which is manifesting as an intellectual Nihilistic philosophy.

This is a fantastic insight, and perfectly put.

A great article. I loved this movie and you’ve given me a few more reasons to

One of the most comprehensive , pertinent , articulate l, relevant and timely “film reviews” I’ve had the privilege to read for decades. Thank you!