The Mythical History of Camino de Santiago

The history and mythology of Europe's greatest hiking trail

In May and June this year I walked the ancient pilgrimage path the Camino de Santiago across the north of Spain. When I got back I thought I'd write something up on my experience and on the Camino itself but I quickly found that I had too much to say. In the case of my experience I decided to make a video where I talk off the cuff about my experience (for those interested I've put the video below). In the meantime I decided to take some time and do my research on the Camino itself — the part fact part myth that make up the history of the Camino and its significance in the development of Europe as we know it.

A Medieval Pilgrimage

The Camino de Santiago is a Christian pilgrimage that dates back to the 9th century. It is one of the three great pilgrimages of Medieval Christianity along with the route to Rome and Jerusalem. Medieval pilgrims were fond of their insignia. Those returning from Jerusalem carried palm leaves and were known as "Palmers", those returning from Rome wore the crossed keys of St Peter and were called "Romers" and those on the Camino carried scallop shells picked up from the coast beyond Santiago and were known as "Jacquets" (Jacques being the French name for Saint James). If you walk the Camino today you'll see these shells on every backpack and every waymarker — it is the Camino mascot.

As far as pilgrimage sites go Rome and Jerusalem are fairly self-explanatory; the same can't be said for this random city in the northwest of Spain but the clue to its pilgrimage status lies in the name. The city Santiago de Compostela is named after Jesus's apostle James the Greater (Santiago in Spanish) whose remains found their final resting place in the cathedral in this city.

And so. since the discovery of these remains in the 9th century this place has exerted a magnetic draw from across Europe and more recently from across the world attracting pilgrims — some in search of healing, some in search of God and others, as was common in Medieval times, sentenced to walk the Camino in lieu of serving time in prison.

The Camino was a Medieval institution. There are castles and churches built by the Knights Templar scattered along the way, there are churches gilded in gold (thanks to pilgrim donations) everywhere along the path and a network of pilgrim hostels (called albergues in Spanish) and the remnants of many hospitals. The popularity of the Camino peaked in the 12th and 13th centuries at the same time as the Crusades were in full swing and a pilgrimage was the coolest thing you could do. Most people couldn't be bothered going all the way to the Middle East however — especially as it became increasingly dangerous in the later 12th and 13th centuries — and so the Camino provided the ideal outing for the aspiring pilgrim.

Many Routes

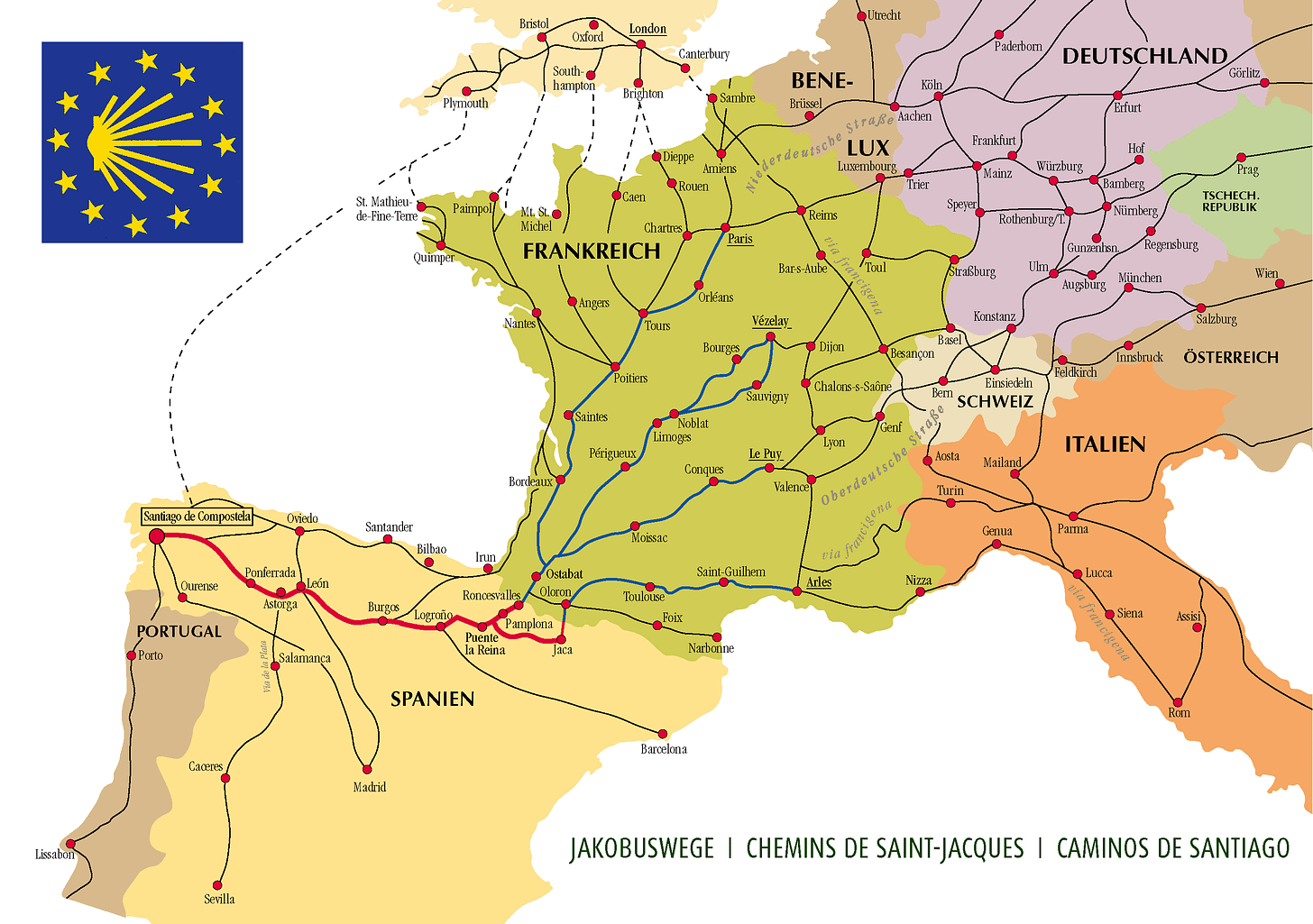

Just as many roads lead to Rome so there are many Caminos from which the pilgrims used to come. The Irish and British Caminos land in northern Galicia at A Coruña and pilgrims walk 75km south to Santiago; the Camino Portugés comes north from Porto; the Via de la Plata comes all the way from Sevilla; but without a doubt the most popular of all by a good country mile is the Camino Francés which today starts from Saint Jean de Pied de Port on the French side of the Pyrenees mountain range and proceeds across the north of Spain making its way slowly but surely to Santiago. This is the route that I walked this year (along with hundreds of thousands of other pilgrims).

After the long first day you've left France behind you and arrived at the Medieval monastery of Roncesvalles — a place famous for seeing the legendary Charlemagne's army given not just one but two beatings by the local Basque people in the 8th century (and later providing inspiration for the oldest epic of French literature — The Song of Roland).

From Roncesvalles it's 790km/490mi to Santiago and another 85km/50mi to the edge of the world at Finisterre. The Camino Francés route passes through four different regions — there's the mountainous Navarre region for the first week; there are a few days in the famous La Rioja wine-producing region centred around Spain's fastest-growing city Logrono and then we enter the massive Castille y Leon region for the next 300 or so kilometres and finally there is Galicia where we finally come to Santiago and beyond it to Finisterre.

One of the most amazing things about the Camino is how it feels like four or five different hikes. There is such a dramatic difference between the different weeks. In the Navarre region there are a lot of hills and a lot of horses with bells around their necks; then in the Rioja there's a sea of vineyards which gives way into Castille y Leon to the flat plains of the meseta with its oceans of wheat and oats and finally Galicia feels so much like Ireland with the dairy farming and small fields and that soft Galician rain (as it turns out the people who settled Ireland in the Iron Age came from Galicia and they must have felt right at home).

At the end of this 500 mile walk you come to the cathedral on the hill in Santiago de Compostela (I doubt I'll ever see more gold and silver in one place in my life). But Santiago isn't the only endpoint. Apparently the old Celts used to have their own pilgrimage in the north of Spain where they would walk to the Atlantic coast for a spiritual encounter with the edge of the world; it was an archetypally powerful place of ritual and initiation. When the Romans came along here — and along the way we walk along Roman roads commissioned and walked travelled by Augustus himself — they built their roads all the way to what they called and is still called Finisterre which in Latin means the "end of the world".

The Legend of Saint James

The story of the Camino is as much myth as it is history and the most mythical element of all is of course how Saint James ended up here in the first place. The story goes that just before his death Jesus carved up the world among his apostles urging them to spread the Word as widely as possible. James was assigned the Iberian peninsula — the peninsula today made up of Spain and Portugal. But at that time it was entirely under the rule of the Roman Empire (the conquering being completed by Augustus in 19 BC).

James travelled as far as Galicia in the far north-western corner of Spain but he wasn't having an awful lot of luck it seems since he only attracted seven disciples. At this time he had a vision from the Virgin Mary — the first in a long Catholic tradition of apparitions by Mary and all the more notable since she was alive and well in the Holy Land. Mary (along with a host of angels) appeared to James and consoled him. According to some versions of the story this apparition was just about giving him a bit of a morale boost; according to others she recalled him to the Holy Land where four years later he became the first apostle to be martyred — getting beheaded by King Herod. This last event is the only part of this myth that appears in the Bible.

The later myths connecting James to Spain which began to appear after the 7th century had to explain how he could both have been in Spain and buried in Spain while also getting martyred in Jerusalem. And so the story goes that some good Christians snuck James's body out of Jerusalem and put it on a boat that with no sails, oars or even sailors (except in some versions of the myth an angel steering the boat) traversed the length of the Mediterranean past the straits of Gibraltar and up along the Iberian coast until it came to Galicia in northwest Spain.

After reaching Galicia, James's disciples — who somehow knew he was coming — took his body off the boat and after many adventures they buried the body on a hill 80 kilometres from the coast. This burial place was forgotten for centuries until in 813 a man named Pelayo — in some stories a hermit in others a shepherd — heard supernatural music and saw a strange star and followed them to a place called Libredon (in some stories a mountain; in others is a forest). He came to the site and upon digging discovered bones and parchment. Realising he had discovered the remains of Saint James and two of his disciples Pelayo rushed off to tell the bishop who quickly came and confirmed Pelayo's finding.

The bishop went to the King of Asturias Alfonso II who made the first pilgrimage to the burial site from his capital at Oviedo. And this route that Alfonso II walked as the first pilgrim has become immortalised as the Camino Primitivo — the original Camino route. Alfonso II confirmed the finding and ordered the building of a chapel on the site. Over the centuries this chapel evolved into the cathedral we have today and around this cathedral grew the city known today as Santiago de Compostela.

It's from these early legends that the "de Compostela" part of the city's name Santiago de Compostela derives. According to some stories Compostela derives from the Latin for burial "componere" since there is evidence of a Roman cemetery on this spot which some date back to Pre-Roman Celtic times.

The other popular etymology of Compostela is from the Latin "compus" meaning field and "stellae" meaning stars so: "field of stars". This is often connected with the star that Pelayo followed but it should also be noted the Camino was also called the Via Lactea which is Latin for the Milky Way — a reference to the fact that the Camino follows the line of the Milky Way to Santiago. As with just about everything to do with the Camino it's something that's shrouded in layers of history, legend, interpretation and counter-interpretation. It's a perfect illustration of the mythic fog that the Camino stands in.

The Islamic Backdrop

Of course all this didn't happen in isolation and there's a backdrop to this story that's well worth discussing. Spain wasn't simply another corner of Europe at this time. A century before Pelayo discovered the tomb the Islamic Empire of the Second Caliphate sent an army across the straits of Gibraltar. At the time the entire Iberian peninsula was under the aegis of the Visigoths who had stepped into the Roman Empire's shoes and taken over the whole peninsula — very much styling themselves on the old Empire.

Within a decade of their arrival in 711, the Muslims had conquered almost the entirety of Spain except for a little slice of land running along the Bay of Biscay in the north of Spain. This is the very parcel of the land that we traverse in walking the Camino today. Where today we have a number of regions, back then there was just one: the Kingdom of Asturias — that last holdout of Christianity in Spain.

The Muslims settled the lands they conquered and named their kingdom Al-Andalus (from which we get the southern region called Andalusia today) and came to be known as the Moors. In the midst of their almost 800 years on the peninsula there were times of great religious tolerance and incredible scientific and philosophical activity which, with the demise of Al-Andalus, gave birth to the modern European intellectual movement sparking the 12th-century Renaissance and ultimately the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century (more of this in future instalments).

This kingdom of Asturias was later to give birth to our contemporary countries of Spain and Portugal but at this time it was a small holdout standing against the largest empire the world had ever seen. When engaged in battle the Muslim armies were infused with a divine zeal — carrying as they were relics of the Prophet Muhammad. With the discovery of Santiago and his relics in Galicia, the Christians of Asturias were only delighted to have their own divine help to enlist in battle.

Santiago Matamoros

And that brings us to the next key part of the Camino myth and that is the legendary sequence of Santiago Matamoros. This part of the mythology begins with a demand for the Kingdom of Asturias to render a tribute of 100 virgins to the Islamic Empire every year. This tribute was duly paid for many years until the king of Asturias Ramiro called a halt to the whole thing. The Muslims obviously weren't too pleased with any of this and so it led to the legendary Battle of Clavijo. The Christians were heavily outnumbered at this battle but they won on account of a miracle — Saint James on horseback fighting at their side and killing thousands of Islamic soldiers hence the title Santiago Matamoros: "Saint James the Moor-slayer".

The consensus among historians nowadays is of course that all of this is pure fiction. It is all part of a narrative of Spanish identity that was formed against the backdrop of the Muslim invasion. Saint James is central to this national identity.

Saint James had intervened in the battle in response the prayers of the king Ramiro who promised that the booty would be shared with Saint James along with the first fruits of the harvest going forward. This was the beginning of the "Voto de Santiago". This offering was reinstated in 1643 by Philip IV of Spain and again by General Franco during his 20th-century reign. The offering continues to this day with the monarch or a member of the royal family coming to the city for the feast day of Santiago on the 25th of July to render a symbolical offering (ofrenda).

All of this attests to the context of the Camino's old esteem. One wonders whether a burial site of Saint James in Belgium or Austria would have caused as much excitement. The myth of the Camino and of Santiago is central not just to the Spanish identity but to the entire Medieval European identity. This little sliver of Christendom in the north of Spain along which the Camino ran and out of which sprang the countries of Spain and Portugal stood against the Islamic invaders. It was an exotic place where mere Christianity collided with the titanic force of history and the Orient.

The Camino reached its peak of popularity in the 12th and 13th centuries after the Reconquista — the Christian conquest of the Islamic Al-Andalus was well underway. The rhetoric behind this so-called "reconquest" invoked the spirit of the Crusades which began in 1096. After the path to Jerusalem became inviable after the Crusades the Camino became the biggest pilgrimage in Christianity. The Knights Templar set up churches and fortifications all along the way and protected the pilgrimage from bandits and brigands (that is until the king of France forced the Pope to have them all arrested and burnt at the stake to get out of paying some loans he owed them).

At its height in the 13th-century there were 250,000 pilgrims making the journey to Santiago from across Europe every year. These numbers took a major dip in the 14th century with the Great Famine of 1315-1317 knocking out most of the continent's food supply for a decade and killing 10-15% of the population. This famine was followed thirty years later by the Black Death which killed between 30-60% of the population. It wasn't until 1500 that Europe returned to the population levels of 1300. And at that point Europe was a very different place. The Renaissance was in full swing, the birth of Protestantism with the Reformation was about to get started and the Spanish Inquisition was well underway. The Medieval world was slowly morphing into the Modern world and so slowly but surely the numbers walking the Camino went downhill.

The Renaissance of the Camino

This decline continued into the 20th century but then a Renaissance began to emerge. It is no exaggeration to say that this rebirth of the Camino can be attributed to the Herculean efforts of one man — Don Elías Valiña.

Valiña was the parish priest of the Galician village O Cebreiro. He did his doctoral thesis on the Camino and as well as writing the first modern guidebook of the Camino in 1982. And years before this he could be seen out across northern Spain with a bucket of yellow paint and a paintbrush painting the arrows that every Camino pilgrim loves and adores — showing up as they so often do in the nick of time to save us from getting lost. He was also the man that started the tradition of Camino pillars that we find all along the way. He worked with mayors, other parishes and the associations of friends of the Way to create the route that we walk today on the Camino Francés.

In the same year as Valiña's guidebook, Pope John Paul II walked a stretch of the Camino into Santiago — another catalyst for the growing popularity of the Camino. Later in the 1980s Paolo Coehlo whose 1988 book The Alchemist launched him to international fame wrote a novel titled The Pilgrimage about the Camino.

Since then the number of people completing the Camino has increased exponentially. From the 37 people who apparently completed the route in 1967, and the writers who walked the Camino in the 1970s without meeting a single pilgrim, the Camino has exploded in numbers and shows no signs of slowing down.

In 2012 there were just under 200,000 but by 2019 there were 350,000 and in 2022 440,000. What the future of the Camino will look like it is hard to say. No doubt there will be more and more hikers out along the trail as the legend of the Camino's magic reaches more and more people. Whether the facilities will be able to handle the increased strain we will have to wait and see but for now it seems that there's no stopping the Camino and no stopping the droves of us that continue to fall under its spell following in the footsteps of 1200 years of pilgrims.