What is Structuralism? | Continental Philosophy

Lévi-Strauss, Barthes and Piaget

Structuralism was a school of philosophy that was at the forefront of the Continental philosophical tradition for a few short years in the 1960s. This time at the cutting edge, although brief, was critical; it marked a turning point, a bridge from the Existentialism that had dominated the Continental tradition since the Second World War into a new intellectual landscape that has often been captured under the labels Post-Structuralism and Postmodernism.

In this article, we are going to be looking at what Structuralism is, why it was so revolutionary and why it was so quickly outgrown.

Saussure

Structuralism can’t be understood without reference to the work of Ferdinand de Saussure. In a previous instalment, we looked at Saussure’s revolutionary reorientation of linguistics with Semiology or as it’s now known Semiotics. This work of Saussure made him the retroactive father of the Structuralist tradition. In the language of Thomas Kuhn, Saussure birthed the paradigm within which Structuralism worked and it was an exemplar of what a Structuralist analysis should look like.

In his posthumously published work Course on General Linguistics, Saussure made a number of important distinctions that laid the groundwork for this tradition.

The most important idea for the purposes of our general overview of Structuralism is Saussure’s distinction between parole and langue. These are two different words for language that have slightly different meanings for the Swiss linguist.

Parole is the trillion and one uses of language as it is used everywhere every day. It is language in motion. But underneath this constantly changing surface of language there is the langue, the structure of the language which dictates the workings of parole. The relationship between langue and parole is much like that between the rules of chess and a particular game of chess. The rules provide a structure that give meaning and order to the individual moves in a particular game of chess.

In the same way the langue provides the structure of language within which our day-to-day interactions occur and derive their meaning.

This distinction between the empirical surface of language and the hidden underlying structure of it was to prove a major inspiration for the French philosophers of the 1960s and 70s.

What is Structuralism?

With that groundwork in place then let’s talk about what Structuralism is.

In the broadest sense, Structuralism is a way of perceiving the human world in terms of structures. This is already familiar to us when looking at the physical world. The natural world whether it’s a supernova, a quark or a gene are individual instances that operate by underlying rules. Each supernova, quark and gene are different – they are the parole of the natural world.

But underpinning them is the hidden structure of physical laws that scientists have unriddled in the past few centuries. From Newton’s laws to the work of Watson and Crick, humanity has been decoding the langue of the natural world – the hidden set of structures that makes the physical world predictable and enables the progression of science.

Structuralism is the transposition of this physical scientific worldview onto the human world. At its core Structuralism is the belief that this human world is subject to such a langue and that we can discern these structures.

Saussure was the pinup philosopher of the Structuralists. His analysis of language gave Structuralists the confidence and the example — in Kuhnian language the paradigmatic exemplar — of how this work might be done.

But Saussure wasn’t the only inspiration for the Structuralists. Much as the Existentialists of the 40s and 50s cast their net back to 19th century thinkers like Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Dostoevsky, the Structuralists cast their net back not just to Saussure but also to Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx.

Marx’s Structuralist reputation comes from his dialectical materialism in which he argues that the underlying structures of society – the labour, class and socioeconomic conditions — determine all the higher activities. Thus religion is opium for the masses and philosophy, art and politics are all surface reflections of the deeper underlying structure of material concerns.

Freud was another legendary proto-Structuralist because he undermined the myth of the free conscious agent that was at the backbone of the Western Judeo-Christian tradition since the story of Adam and Eve. Freud showed that who we are as individuals is determined much less by the surface of the mind – by the words and thoughts we consciously think about ourselves – than it is by the deep hidden structures of the unconscious mind.

But moving beyond Saussure and the proto-Structuralists, in the 1960s and 70s, the Structuralists-proper applied this type of analysis to fields as varied as psychology, anthropology, history and sociology.

The Structuralists

The ideas of Structuralism are far too varied and disparate to fit into one episode. Like Existentialism, Post-Structuralism or Analytic Philosophy, it is a catch-all term that serves more as a useful container than as a tightly defined set of shared principles. That being said, it is worth giving an overview of who the major players were and how they applied the ideas of Structuralism.

The pioneer and most famous of the Structuralists was Claude Lévi-Strauss who, in many ways, was to Structuralism what Sartre was to Existentialism.

Levi-Strauss’s stomping ground was cultural anthropology. He left France to teach in Brazil and spent a lot of time in the Amazon observing indigenous tribes.

He examined social phenomena such as kinship structures, myths, cooking practices, religion and ideology and searched out the underlying structure. The most famous Structuralist approach to mythology is without a doubt Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With A Thousand Faces. Campbell, though not a Structuralist, was strongly influenced by Lévi-Strauss and his work is the perfect example of the Structuralist project of unearthing underlying structures in this case exposing the monomythic structure of the hero’s journey that hides beneath the surface parole of a million and one individual myths.

As well as Lévi-Strauss there was the legendary psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan who explored the philosophical implications of Freud’s work and applied mathematical logic and topology to the psychology of humanity.

There was Roland Barthes who applied Structural analysis to cultural relations most famously in his highly entertaining book Mythologies in which the French philosopher applies Structural analysis to everything from wrestling and soap to margarine and the appearance of Ancient Romans in Hollywood movies.

There was also Michel Foucault whose early work — despite his later acrid comments to the contrary — are classics of Structuralist thinking in which he applied structural analysis to the history of punishment, mental illness and to knowledge itself.

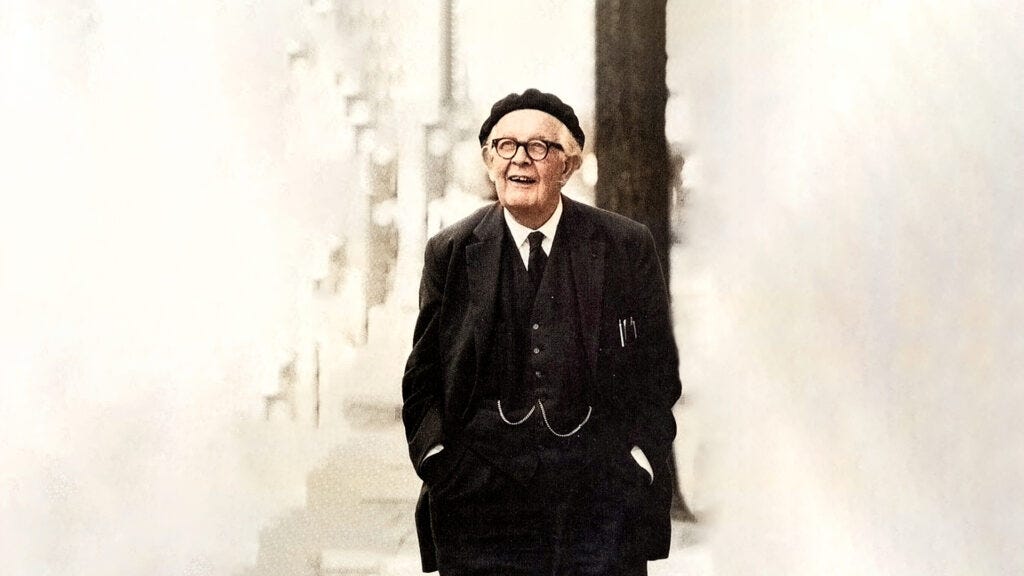

Outside of the French main-line of Structuralism, the most famous of thinker in the school was a scientist — the developmental psychologist Jean Piaget. In a previous instalment, we looked at Piaget’s model of childhood development and at the four stages of development that each child goes through on the way to adulthood. Piaget is unusual among the Structuralists in that he is a hard scientist rather than a social scientist and is a part of the scientific grand tradition rather than the philosophical one.

But in 1970 Piaget wrote a book called Structuralism in which he explored the connections between his form of Structuralism and fields such as mathematics, physics and biology. In the last couple of chapters of the book he turns his attention to Structuralism of his colleagues in the social sciences. While has a lot of praise for Lévi-Strauss and a lot of criticism for Foucault, ultimately he finds more bathwater than baby in the applications of Structuralism in the social sciences.

Piaget and the Failures of Structuralism as a Science

The work of Piaget serves to highlight a lot of what went wrong with Structuralism. Structuralism is the belief that there is an underlying structure that human activities adhere to. This abstract nature means that these structures are not directly observable. All of which begs the question: how do we uncover these structures?

While the work of Lévi-Strauss caused great excitement and, like most of structuralism, was an electrifying intellectual journey, it is ultimately froth. Lévi-Strauss’s work in anthropology is praiseworthy more for the inspiration it provided to potential anthropologists rather than any rigorous conclusions that have stood the test of time.

As early as 1970, the Cambridge University anthropologist Edmund Leach famously wrote of Lévi-Strauss:

“Even now, despite his immense prestige, the critics among his professional colleagues greatly outnumber the disciples.”

Lévi-Strauss brings to mind Aristotle’s pioneering work in science. He was attempting to discern the structure to the natural world but, working from the armchair, his results were far from rigorous. As Kuhn would put it: though he was a scientist, the net output of his work fell far shy of the label science.

By comparison the work of Piaget is a Structuralism that is supported by a solid skeleton of science. And while Piaget’s work is far from criticism-free, it has behind it the rigour of decades of experiments and a whole field of scientists working in the same direction. Piaget’s work instantiated a paradigm in the field of developmental psychology that the work of Lévi-Strauss never attained in academic anthropology.

This was the failing of Structuralism in the social sciences. With the works of Lévi-Strauss, it never attained a rigour that deserved the label science and yet it was the all-important stepping-stone from which Post-Structuralism jumped off.

Derrida’s Criticism

In 1967 work Writing and Difference, Jacques Derrida dealt a death blow to Structuralism that marked the beginning of Post-Structuralism. His criticism of the school comes at it from a different angle to Piaget’s and yet there is a surprising overlap between their evaluations.

Derrida sees Structuralism as going way back beyond Saussure to Plato. It is the history of Western metaphysics seeking the eternal unchanging structures. He is referring to Plato’s Ideas– the eternal unchanging Forms out of which all particular instances emerge.

Thus in Plato we have the langue as the archetypal realm of the Ideas and we have the material world as the parole of these Ideas. All chairs are individual instantiations of the archetypal Idea Chair just as all good deeds are individual instantiations of the archetypal Idea of the Good. And so you have the langue of the Ideas and the parole of the immediate individual experience.

Derrida criticises this Structuralist idea as being myopic and missing out on change and individual cases in its focus on the structure.

This dovetails nicely with Piaget’s criticism of Structuralism in the social sciences. In his 1970 book Structuralism Piaget criticises Levi-Strauss’s conception of structure as static, atemporal, anti-functionalist, and leaving no place for “the activity of the subject.” He sees his own Structuralism as being completely at odds with this.

Coming from a more traditional scientific background it is hard to think of human developmental stages as being atemporal and static rather than evolutionary and changing over time.

But this is what Piaget and Derrida find fault with in the main-line of Structuralism — it is an unchanging atemporal straitjacket that human life must abide by ad infinitum.

Piaget comes at it from a scientific angle while Derrida comes at it from a linguistic one but both criticisms point to the same fundamental tension, a tension that has been in Western philosophy even before Plato: the interplay between Being and Becoming between change and order. It’s the same puzzle that Parmenides, Heraclitus and the other Presocratics that followed them were all wrestling with and it seems the same crisis reared its head once again in the 20th century Continental tradition. In the article on Phenomenology we saw this same disjoint between Heidegger and Husserl and it’s something we’ll be exploring in more depth as look deeper into Heidegger and into Post-Structuralism.

Summary and Conclusion

To summarise then Structuralism was a branch of French or Continental Philosophy that had its heyday in the 1960s with the works of Levi-Strauss, Lacan, Foucault and Barthes.

Structuralism argued that there is a structure beneath the surface reality that explains reality more accurately than the empirical study of this surface. The Structuralists took as inspiration and exemplars the works of Marx, Freud and above all Ferdinand de Saussure.

Inspired by this approach, Lévi-Strauss sought to uncover the underlying structures in his field of anthropology – whether that was in mythology, kin relationships or cooking practices. Lacan sought to push the envelope on Freud’s analysis of the unconscious while Foucault with his Epistemes attempted to use structural analysis to understand the history of punishment, madness and knowledge.

Ultimately Structuralism with its rigid atemporal conception of human life was outgrown but it provided a bridge between the Existentialist tradition that had ruled in the 1940s and 50s to the so-called Post-Structuralist and Postmodern trends that emerged in the 1970s and 80s.